Grief: How to Cope with Terrible Loss

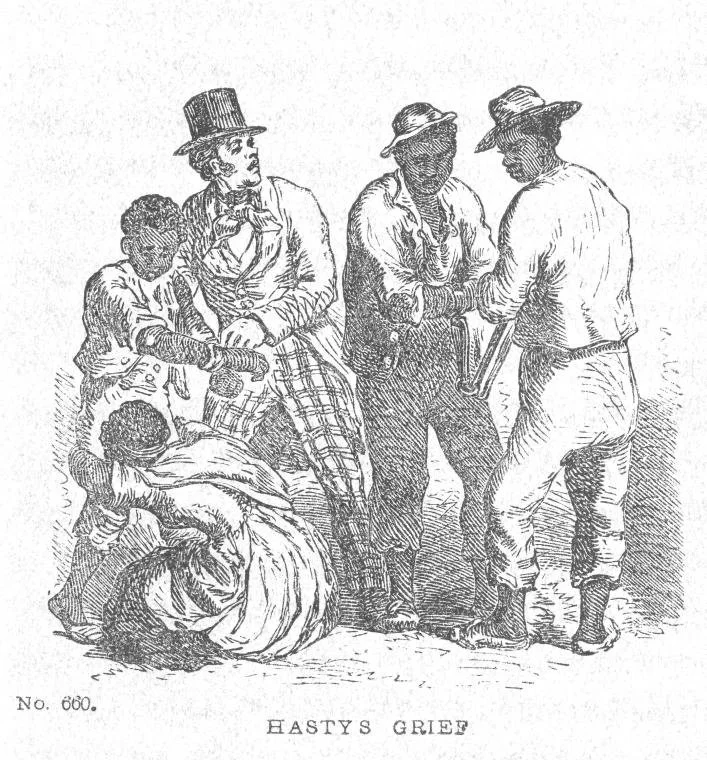

Hastys Grief (1860), Located at New York Public Library. This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published (or registered with the U.S. Copyright Office) before January 1, 1929.

WHAT IS GRIEF?

Grief is the experience of unacceptable loss.

It is different from all other kinds of sadness.

UNACCEPTABLE LOSS, WHAT’S THAT?

There’s a scene in a classic movie about World War I. A soldier is wounded in battle and brought unconscious to a field hospital. A couple of soldiers, buddies, are standing at bedside. The wounded soldier opens his eyes, points his finger, and says, “My leg hurts.” One of the buddies says, “Your leg was cut off.” After an instant of silence, the wounded soldier’s expression changes from shock to horror. He wails, “No!”

IS SADNESS THE SAME AS GRIEF?

Both are about loss. The significance of the loss, its meaning, is different for sadness and grief. Sadness by itself doesn’t challenge a person’s identity, purpose or beliefs. It’s acceptable even though the loss can matter a lot. Here’s a little story about sadness:

For at least a hundred years, the streets of Milwaukee were lined with big, beautiful Dutch Elms. Then a beetle arrived. Disease spread. Almost all of the trees were cut down. A lot of us felt very sad.

MOURNING

Mourning is another word for grieving. It is a journey towards (and away from) acceptance. Its spiritual nature is universal. The practices of grieving are as varied as there are cultures, and as unique as is each individual.

JOURNEY TOWARDS ACCEPTANCE

There’s a saying, “Time heals.” Healing does take time, but time passes whether or not anything else happens. It takes time to walk from one street corner to the next. It’s the walking that gets a person to the destination. A journey is a walk that has spiritual significance.

ACCEPTANCE MATTERS

My parents died, about two years apart, years ago. A brother of mine and I took care of each until their last breath, with the help of hospice. Our Mom died first - at age 89 - and my main feeling was relief, her suffering was over and so was ours. When our Mom was good and connected to life she was an angel, and after she was bad she had didn’t recall the terror or recognize the damage that we, her children, absorbed. I had grieved the loss of her love over many years before her death. Our Father was a similar mix of good and bad, with a totally different style that fit his personality. In his 60s he became increasingly nice and when he died I felt immense loss. Now I simply choose to emulate the good and not the bad. A decade later, the brother with whom I had always been most connected died of cancer, it was rapid - about 4 months. I wailed when I first heard. My wife thought one of my kids had died. I miss him. At different times in our lifetime together we were buddies, other times we were estranged. We ended shared life as dear friends - a “ripened” * relationship.

* ”A Matter of Death and Life”, Irvin D. Yalom and Marilyn Yalom, 2021

Montage by Victor Bloomberg, October 6, 2019

Types of Grief

LITTLE GRIEF

Repairing broken pottery (1850), Located at New York Public Library. This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published (or registered with the U.S. Copyright Office) before January 1, 1929.

We all know Little Grief. We get over it quickly. For example, a favorite coffee mug is dropped and broken. “Maybe I can glue it back together.” Yea, but I can’t use it. Should I toss it? Or maybe, I can look at it and accept not drinking from it. I’ll change how I see it. It can be like Japanese art called Kintsugi.

BIG GRIEF

Montage by Victor Bloomberg, October 6, 2019

We all know Big Grief. It overwhelms.

Suffering is private.

Yet we share it through communal rituals.

COMPLICATED GRIEF

Montage by Victor Bloomberg, August 26, 2015

The opposite of complicated is simple. Does simple grief exist? Yes, it might be simple when the death is expected and peaceful. Simple grief is common when the person’s life was fulfilled and you feel grateful for the life that was (even though you feel sad that life has passed).

“Not simple” does not cover all of the different kinds of complicated grief. That’s because even when the person who died might have been free of pain at the end, the survivor could still have injuries from their shared past. The person who died might have fulfilled their potential as best as could have been, but the survivor might be troubled by foiled aspirations. A survivor could be burdened by present-day circumstances - and there is recurring pain rooted in the past with the person who died. Sometimes grief reappears as we go through phases of life or events shake us. Mourning can become complicated.

Grief and Depression

Grotto of Sarrazine near Nans sous Sainte Anne (c. 1864) Gustave Corbett. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Depression can have its beginnings in grief. Or, its origins might have been earlier and then grief arrived. Depression can complicate mourning.

WHAT IS DEPRESSION?

First, a couple of links for good medical, science-based discussions of depression:

National Institute for Mental Health https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression/index.shtml

Mayo Clinic https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/depression/symptoms-causes/syc-20356007

Imagine you, your family and your village lived somewhere for generations and it was very nice. There was clean air, fresh water, plenty of food and places to enjoy. Then the climate changed in a big way. The Ice Age changed everything. Outdoors people had to spend more and more time in caves to escape the cold. There was less food to eat and favorite places disappeared. And it never got better, only worse. There was no escape. So you lost interest in the things that you used to like. Appetites of all kinds decreased. Cooped up in small spaces, there were more arguments. It became easier to sleep more and do less.

This is what depression is like. It is one response to inescapable, overwhelming circumstances. The situation might be easy to describe so that others can see it. For example, depression could be a response to a chronic illness that only gets worse. Other times, the “Ice Age” is private, maybe secret. There might have been childhood neglect or abuse, and now an adult suffers from depression. The “Ice Age” can be a sense of hopelessness about the future, part of a spiritual struggle for meaning in the midst of injustice and destruction. Sometimes it’s a mystery. Psychotherapy can help.

Grief, Expected or Sudden

Illness can give a person an opportunity to imagine death before it happens, and so the loss is anticipated. A warrior sent into battle dies while away, and the notice given the family is not a shock. In both situations, the loss is grievous but not surprising.

Niijima Jō sensei rinju-zu by Kubota Beisen (c. 1890) Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Senseless, wanton separation or death is a severe spiritual crisis for the survivors left to live, apart and alone. Communal ritual and family faith provide support and strength for the spiritual struggle. But, when the loving attention subsides, the private pain and any accompanying social injustice continue. Sometimes a private tragedy is rooted in a social problem.

Le Suicidé by Édouard.Manet (c. 1877) Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Persons mourning expected grief provide an example of coping that can be helpful to anyone jolted by sudden loss. People join “find the cure” type organizations. For sudden loss, “Mothers Against Drunk Driving” (MADD) was organized. There are countless examples of transformation of suffering into organized purpose.

These two kinds of grief, expected and sudden, challenge individuals, families, friends, and communities in two distinct ways. The two different ways can be posed as questions:

WHAT TO DO? HOW TO BE?

Grief: What to Do

Montage by Victor Bloomberg, January 4, 2023

We’re going to talk about action that is practical after community ritual is over and your family and friends are back to their routines. The “to do” list is necessarily general. An individualized plan is best made with the support of a counselor.

This list is called The Self-Care Five

Eat Well

Sleep, Rest and Relax

Exercise and Purposeful Movement

Have Fun With Others

Spiritual Time

If, despite your best efforts, you can’t do The Big Five or you’re doing them and can’t reliably function well, then it’s time to consult your physician.

Grief: How to Be

Earth Rise, Bill Anders, Apollo 8, NASA December 24, 1968

We’re going to talk about spirituality. One thing in common among all religions is guidance about the meaning of a person’s life. Many people reflect on this without a religious community. So we see that spirituality is universal, even while it is expressed in different ways. A teenager once asked me, “How do you know if something is spiritual?” My reply, “When it has to get done, it’s a chore; but when it’s simply meaningful, it’s spiritual.” So we see that it’s not the activity, but rather the quality of the experience. Sometimes I cook the meal and it’s a chore, other times it’s a way to be loving.

Chores and spirituality can overlap. Lovingkindness can be shown by doing chores for someone who is grieving. But, what about the times when there’s nothing to do? Maybe I’m the person grieving and there’s nothing for me to do. In either case, I need to know how to be.

Among the most meaningful experiences is when someone pays attention with respect. Then the person is seen as a human being with dignity, an individual with their own spirit. It is not a transaction that can be measured with a plus or minus. Rather it is tuning into the emotions and meaning of the moment, simply to be supportive. This is the way to be.

Grief and Psychotherapy

Counseling provides a safe place for you to talk about things that matter, to resolve a specific situation. Psychotherapy reflects on experience, explanations for it, and beliefs about what it means. There is often a back-and-forth between counseling and psychotherapy, whether the session’s focus is grief or another challenge.

Consider counseling and psychotherapy to be work for each person in the session. There is dignity in work.

When you feel safe, you know that no harm will be done. Trust is a reputation based on the reliable history of safety with a person. Okay, you feel safe and trust the psychotherapist. Then what?

Here’s what happens. As you reflect on the grief during the session there will be special moments. These appear spontaneously, over and over again. In that moment, the pain in the here-and-now and from the there-and-then is felt while you feel safe in the present. Feelings are released, and reflection follows. Psychotherapy supports grieving so that the loss becomes tolerable; this opens a pathway. The path is a back-and-forth between the pain of unacceptable loss and the ability to tolerate the pain. The meaning of loss can change, the loss becomes acceptable because its significance is different. For example, a mother of a child who was murdered joins a nonprofit to support other parents whose kid was killed. This is one way that sadness becomes a source of compassion, power guided by love.

Chaco Canyon, Photograph by Victor Bloomberg, October 21, 2022